Profit = Income – Expenses

Get familiar with this business equation because it’s not going anywhere!

As a market gardener, you have many different enterprises, or crops, each with its own Profit equation.

All of the individual farm activities are combined to create an average annual profit (or loss) for the entire farm.

If you’re not sure what I am talking about, check out this article.

Unless we know how each part contributes to the whole ( carrots vs. beets vs. lettuce vs. beans, etc.), we are operating in the dark and have a tough time figuring out how to increase overall net profit.

It’s pretty unlikely that all farm activities contribute equally to your market garden’s overall profit.

Some crops are more profitable than others, and some may even lose money.

Once we know which farm enterprises are making money and which are not, you can increase overall farm profitability that much easier.

Much of the information provided in this article is from The Organic Farmer’s Business Handbook by Richard Wiswall, which I highly recommend purchasing for yourself for its invaluable information.

So, if we know how much profit we want to make in a season, there are two variables we need to figure out in order to make that happen, income and expenses.

Tracking Income

Market farm sales come from many different sources and are tracked in different ways.

To truly quantify the income variable of the profit equation for each crop, we need to know how much of the product leaves the farm and what its sales value is.

Wholesale Accounts

Sales to wholesale accounts (e.g. restaurants) are the most easily monitored because both you and the buyer most likely use invoices as a form of record-keeping.

Duplicate invoices are filled out listing each product and price. Both you and the buyer keeps a copy for your records.

Included on the invoice should be the items, quantity, and dollar amount.

The use of duplicate invoices creates an easy to follow paper trail.

Farmer’s Market

Often at the close of a Farmer’s market, growers are more concerned with packing up and getting home than knowing exactly how many cabbages were sold.

Tracking each crop’s sales at every farmer’s market is not very difficult or time-consuming. All that is required is getting yourself into the habit of data collecting (time to nerd out!)

Two pieces of information are needed: a beginning inventory of what items (and their amounts) that were brought to the market, and an ending inventory of what is left at the end of the market.

Five minutes before packing up, take your list of items that you brought and record what is still remaining on the tables. Then, you can pack up and go home.

Time-wise, recording your beginning inventory on a sheet of paper on a clipboard may take you a couple of minutes. Marking off ending inventory takes another couple of minutes.

When you count your money earned from the farmer’s market, write the total sales figure down on the inventory sheet for future reconciliation.

You don’t need to do the math right then and there, you can do it when you have time later, which may even be in the off season. The point right now is to track it.

Farm Stand

Tracking farm stand sales is similar to the farmer’s market procedure.

Record what is at the stand at the beginning of each day, add in any product brought in during the day, and finish by noting ending inventory.

Again, you do not have to calculate each crop’s sales right away, it can wait until you have more time.

None of this data collecting is terribly time-consuming, but it does have to occur on a regular basis.

CSA (Community Supported Agriculture)

CSA income is another easy to track sales. All you need is a paper and pen.

Every week’s CSA share is made up of what’s available that week and what the customer likely would prefer.

CSA growers determine which crops, and which amount of each will constitute a share.

Simply record this CSA share information in a notebook (or spreadsheet) to be compiled later on with other sales accounts.

Sales Spreadsheet

All income coming into the farm should be accounted for.

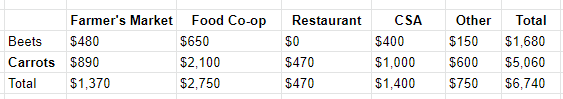

Data from all your sales outlets are now compiled into a Sales Spreadsheet (example below).

Accounts are named across the top, with different crops listed along the left side.

The Sales Spreadsheet is a valuable one-page summary of all your sales income.

You can monitor trends in each account, and in each crop.

Plus, you have a grand total for all sales.

Comparing sales from year to year, or even more often, is helpful for future planning.

Computers make this task a snap, but even with pencil and paper only a few hours each year is required to calculate this invaluable information.

Tracking Expenses

Tracking expenses sounds pretty simple. You buy seeds, you get a bill for them, you write a cheque for payment.

You know how much your beet seed costs, how much you paid for rock phosphate, and the expense of each 25 lb plastic bag.

But what about all the expenses in between purchasing the seed and packing the beets into their 25 lb traveling bag?

Planting the seed, weeding the crop, irrigating when needed, and harvesting constitute most of the costs in raising a crop and must be accounted for.

Systems need to be in place for tracking those expenses that detour the conventional itemized paper trail.

Paid bills are easy to break down into expenses for different crop budgets, but your own labour and your employee’s time require extra documentation.

At the end of the season, when you actually have time to see what was making money and what wasn’t, you will want to have accurate info at hand from the previous growing season to create individual crop budgets.

The labour input for each crop spans months of work, often sporadically, in bits and pieces.

Recording the information isn’t all that time consuming, but it needs to be done on a regular basis throughout the year.

The Crop Journal

This will probably end up being one of the most important books on your market farm.

It can be just a basic pocket folder with loose-leaf pages inside, one page for each crop, arranged alphabetically.

Anytime a task is performed on a crop, it is recorded on the appropriate page in the Crop Journal.

It’s simple and quick to do once you get in the habit.

All info necessary for later budgeting (and future planning) is written down in the Crop Journal.

Preparing soil, seeding, cultivating, and harvest are all recorded.

Example:

Information is recorded as it happens (keep it in your pocket at all times!), usually at the end of each day. But, if you have a memory like mine, you might want to record your info right on the spot.

It doesn’t take long, especially once you get into the habit.

The info in the Crop Journal is only recorded, not yet tabulated.

The math of each crop’s budget comes later, but the info needed for it is documented as it occurs.

The elusive component of labour can now be easily calculated for individual crop budgets.

The important thing about record keeping in the Crop Journal is that it shows information for each crop in hindsight.

The numbers from this year will hold pertinent information at the end of the year, and for years to come. The data can also be used to project future budgets of possible new enterprises.

This chronological log of each input for a given crop can now be used to accurately track expenses in the Profit = Income – Expenses equation.

Creating A Simple Crop Budget

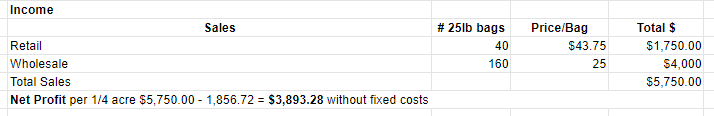

Now that you have accurately tracked your income and expenses for each individual crop, you can uncover the true cost of production for each crop and see what kind of profit you made (or didn’t make) at current prices.

Simple crop budgets do not allocate for fixed expenses such as phone, advertising, taxes, mortgage interest, insurance, electricity, etc.

These expenses are spread out over the whole farm operation and can be viewed as constants.

That being said, the simple crop budget doesn’t tell you exactly your true costs of production but it will allow you to compare crops side by side to rate their relative profitability.

This offers incredibly useful information you can use to improve your bottom line.

You can drop the crops that aren’t producing a good profit if you choose to, or tweak the Profit = Income – Expenses equation by raising prices or decreasing costs to see if you can squeak out a little more profit from a particular crop.

Example:

The information for your Simple Crop Budget is primarily taken from your Crop Journal, so make sure you are tracking your info accurately!

You may just find that demand is high for a single profitable crop, so you can focus on growing that one crop over other less profitable ones.

Index of Profitability

Once you figure out the profitability of your crops using your simple crop budget for each crop, you can easily see your top sellers in order of their profitability per acre.

The single sheet of paper that lists all your crops in order of net return is priceless.

The Index of Profitability drives management decisions, from planting to harvest.

New markets are sought for top earners, while some crops are dropped altogether.

Once a farm manager is privy to such useful information, bottom-line profits for the entire market garden operation rise dramatically.

Be profit-driven, not market or production-driven.

Bottom Line

All this number crunching may seem like a giant pain in the patooty, but it is sooo worth it.

You want to make money as a market gardener, right?

Well, keeping accurate records and using the information to drive your decisions is how you will become, and stay, profitable.

Again, the info in this article is from The Organic Farmer’s Business Handbook by Richard Wiswall. I highly recommend you purchase it for yourself because the information is invaluable.

Do you have a concise way of collecting data on your market farm that you would like to share with us? Please leave any and all helpful info in the comments below. Thanks!

Stay Local,

Kathy & Jon

your friendly neighbourhood growers

0 Comments